Vaché serves in the 60th Divisional Train of the British Army.

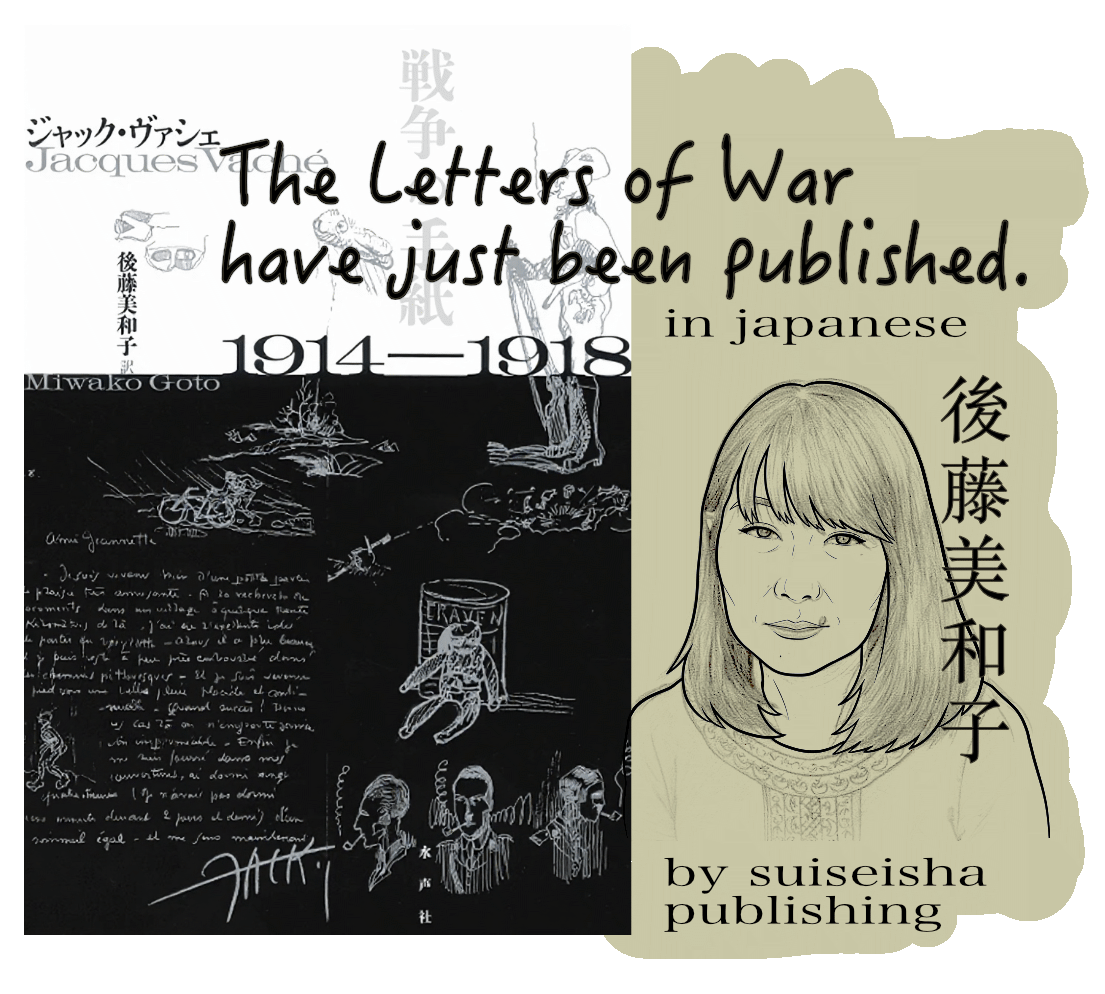

JACQUES VACHÉ

1895-1919

1895-1919

1896-1930

Private collection

1897-1978

a.k.a. Jean Sarment

Private collection

1895-1919

Private collection

They have their conventions, their codes, and their personal arrangement with the French language. Their sense of values and hierarchies. For example, they have established a social order. At the top, the “Mimes”. Why? Because they like the word. It evokes the “mystical grandeur of silence expressing itself”, as Jacques Bouvier [alias Vaché] defined it. Below the Mimes, are the Sars, a homage to Péladan, to the “Rose-Cross” esoteric group, to everything one desires, which they don’t attempt to specify. Below them: men (homo vulgaris). Below men, “sous-hommes” (undermen), below undermen, “surhommes” (supermen); further down the ladder the “sous-off” (non-commissioned officers), and on the last rung,

mired in shame and ignominy—another delicate idea of Bouvier’s— “générals”. They intentionally chose not to use the correct plural form [généraux in the French]. […] Only Bouvier persisted in asking if one could perhaps find a designation for his father (a colonel) —existing below the “général”—which would make this small, nervous, authoritarian man, highly decorated and advanced in age, and undoubtedly very weary, something like an “untouchable”.».

Jean Sarment, Cavalcadour, 1977.

Sarment would also evoke these youthful years in his first novel, Jean-Jacques de Nantes:

Nantes Public Library, ms 3461

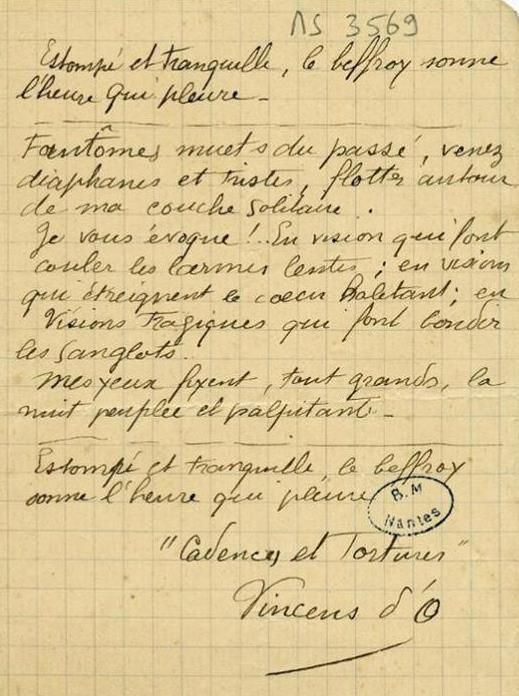

Nantes Public Library, ms 3569

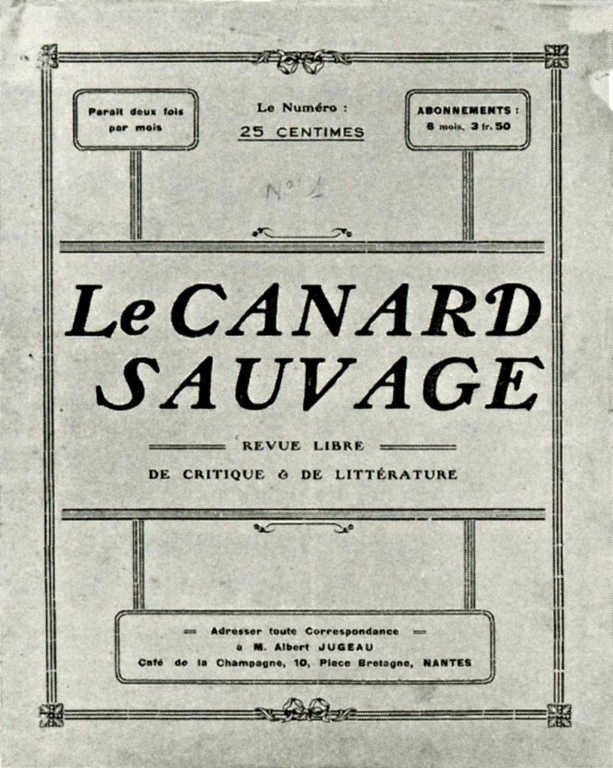

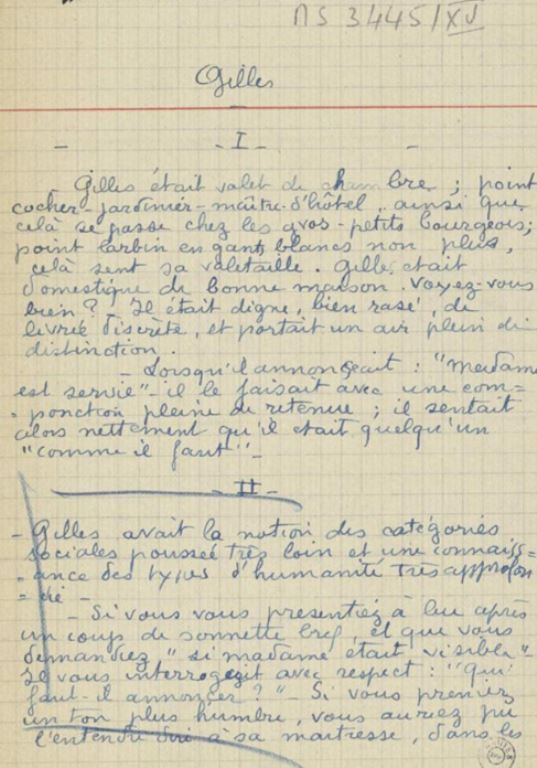

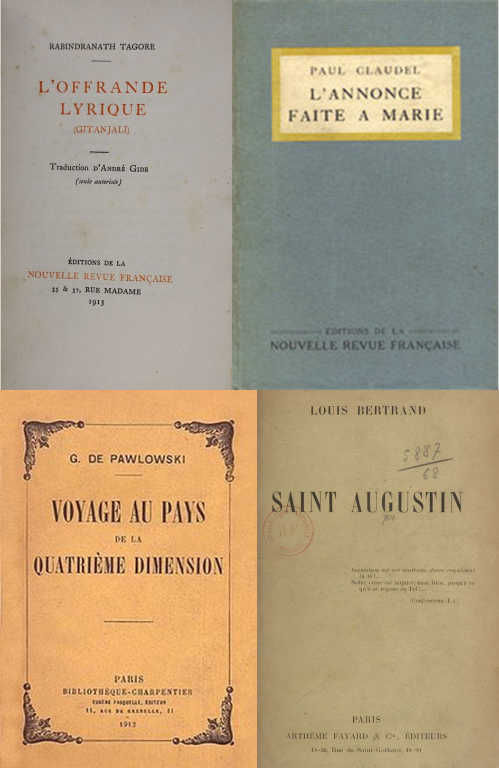

The Sârs however, did not abandon their literary aspirations: they founded a second review called Le Canard sauvage (The Wild Duck), which edited four reviews between late 1913 and mid-1914. Vaché contributed with poetry Gilles – a humorous tale of social satire, and a regular book column, including one he had enjoyed very much, Voyage au pays de la quatrième dimension by Gaston de Pawlowski.

Private collection

Read the full text in the collection of short stories Les Solennels written by Sarment and Vaché (with the exception of Gilles written by Vaché alone).

Nantes Public Library, ms 3445/15

Read Le voyage au pays de la quatrième de la dimension by Gaston de Pawlowski

Read Saint Augustin by Louis Bertrand

‘Each person would add a verse, or two, if inspiration was present.

HARBONNE [alias Hublet] – I had a heart, I had a soul

BOUVIER [alias Vaché] – Listen to my epithalamium.

HARBONNE – My soul departed […] amongst the trade winds

PATRICE [alias Sarment] – I looked for my soul everywhere

BOUVIER – there where the bateaux mouches brought me…

BILLENJEU [alias Bissérié] – To the land of the Eskimos and the Kalmyks.

PATRICE – In my suit with gold buttons.

BILLENJEU – I went to the pink pole

BOUVIER – the pink pole of the North Pole

HARBONNE – I drank the mirrored dew of the evenings…

BOUVIER – and then the incense from the burner…

When war was declared in August 1914, the Sars were all around twenty years of age. The group would be separated due to the international conflict. Discharged, Sarment was the only one of the group not to have experienced combat: he pursued his theatrical career in 1915, in Paris. Bissérié, Hublet and Vaché were conscripted: Hublet would never return home, fatally injured by shrapnel fire on 27 October 1916. A student of medicine in 1914, Bissérié served as a military nurse during the conflict and following the armistice became a doctor, with a serious morphine addiction. He would die in suspicious circumstances in 1930.

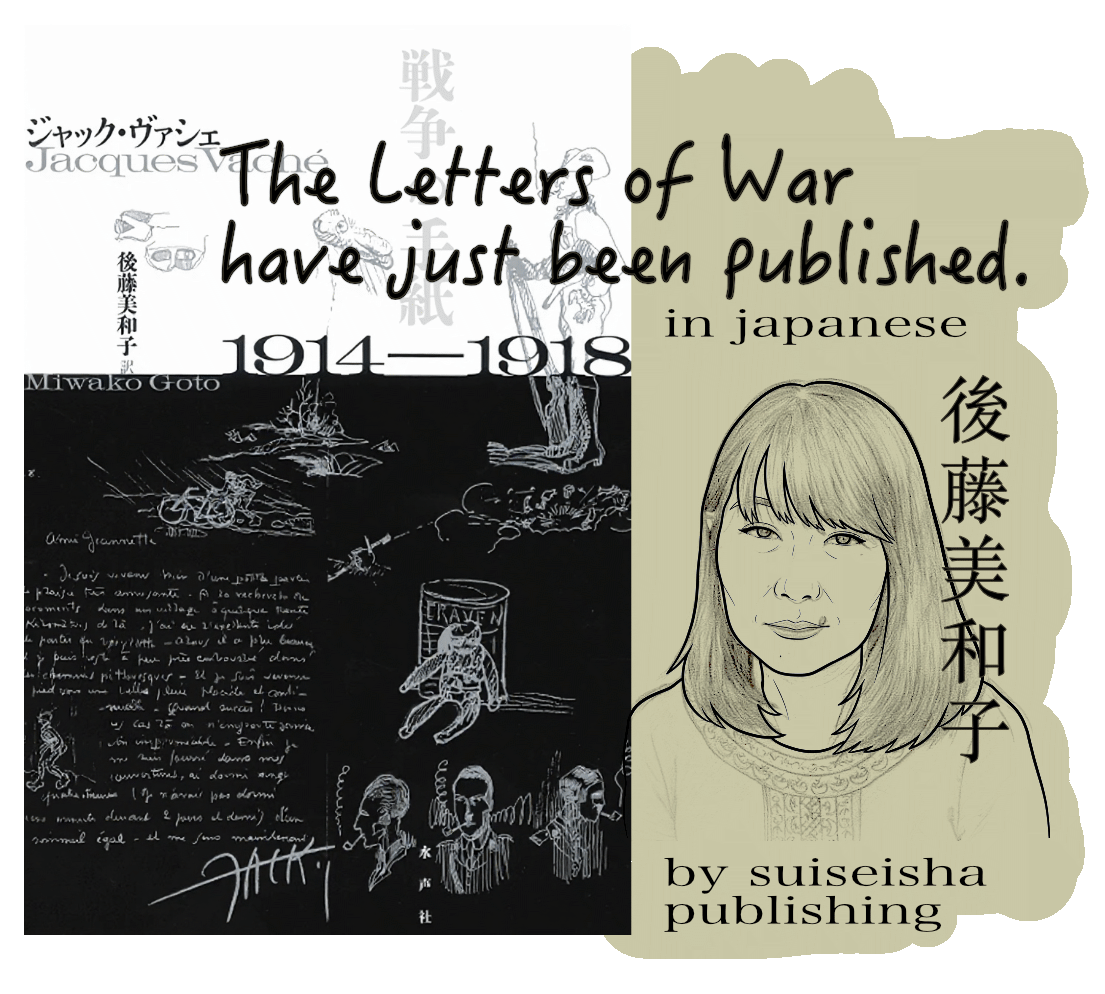

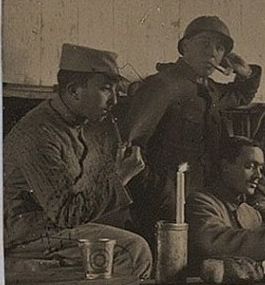

Jean Sarment, Pierre Bisserié and Jacques Vaché

Nantes Public Library, ms 3448/10

Private collection

(July 1917, residing with the Derrien family)

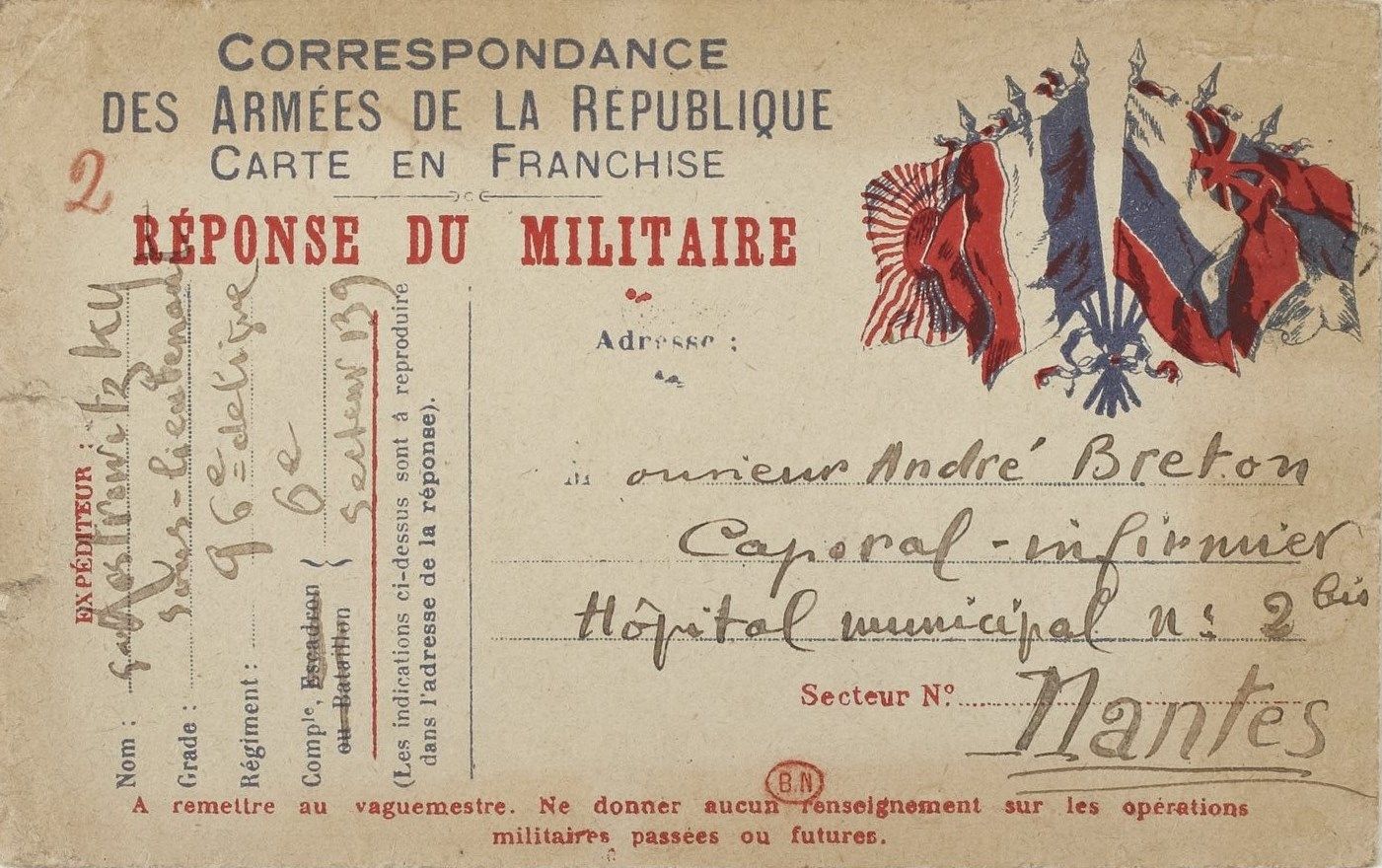

Nantes Public Library (former collection of André Breton)

(July 1917, residing with the Derrien family)

Nantes Public Library, ms 3455

July-October 1916

Vaché serves in the 60th Divisional Train of the British Army.

October-November 1916

Vaché serves in the 2/13th (Kensington) Battalion, London Regiment..

November-December 1916

Vaché serves with the Australians as part of the 34th Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force..

January-September 1917

Once again, Vaché serves the British attached to the 2/5th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry.

During this assignment, he takes part in the second Battle of Bullecourt, early May 1917.

He deserts his post for a period of two days, a sign of his increasingly rebellious attitude towards the military authorities, which earns him a prison sentence of a few days at the beginning of September 1917, followed by a change of assignment.

Septembre-December 1917

Vaché serves for the 2/6th Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment..

January-April 1918

Vaché remains in the service of the British Army but attached to a French officer working as a liaison with the Fifth Army.

April-May 1918

Vaché temporarily serves the American Army, as he claims in one of his letters to Breton.

May-July 1918

Vaché becomes an interpreter for the 157th Brigade of the 52nd Division of the British Army.

From 26 June to 27 July, he is given a prison sentence for an unknown reason. He carries out his sentence at the British camp at Boulogne-sur-Mer.

August-November 1918

At the end of August, Vaché reintegrates the French Army and is assigned to the 14th Squadron Train of Military Equipment. He occupies the post of mail officer at the Directorate of the Military Road Service in the 178 postal sector, the headquarters of the 6th Army at Château-Thierry. He holds this post when he participates in the liberation of Belgium, from where he writes his last known letter.

Private collection.

This drawing by Vaché is more than likely a portrait of his aunt Louise Guibal, a nurse at the temporary hospital, situated a number 103bis on the rue du Boccage (the drawing belonged to her son Robert before the latter donated it to the public library).

Nantes Public Library, ms 3341

It is not unreasonable to imagine that Vaché may have held in his hands certain letters written by Apollinaire addressed to Breton, while the latter was posted at the rue du Boccage.

Read the correspondence between Apollinaire and Breton on Gallica and in the Trésors de la bibliothèque André Breton catalogue.

Given its date, this gouache which belonged to Breton had probably been given to him by Vaché towards the end of his stay in Nantes.

Private collection (former André Breton collection)

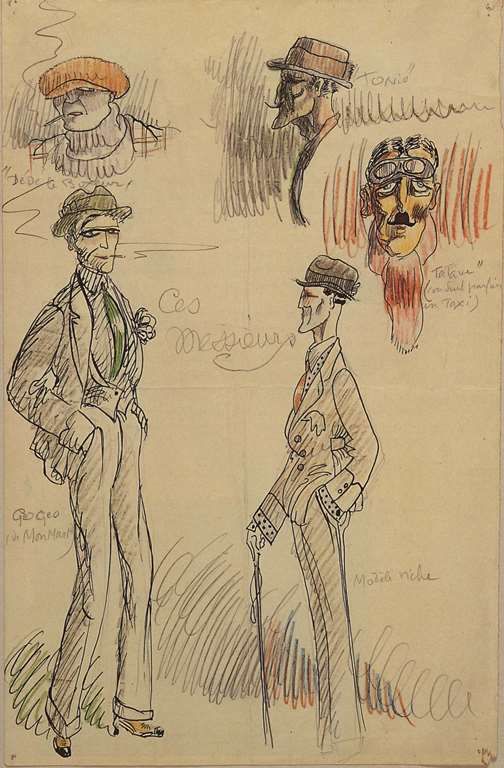

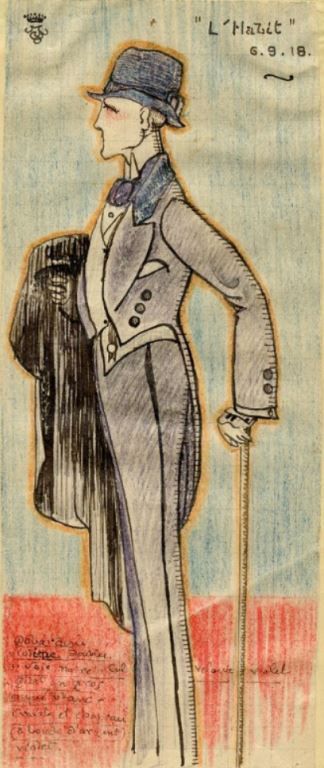

‘At the beginning of 1916, I was mobilized as a provisional intern to the centre of neurology in Nantes, where I made the acquaintance of Jacques Vaché. He was undergoing treatment at the hospital on the rue du Boccage for an injury to his calf. A year older than me, he was a young man with red hair, very elegant, who had taken classes with Mr Luc-Olivier Merson at the School of Fine Arts. Confined to bed, he spent his time drawing and painting series of postcards for which he created some unusual captions. Masculine fashion was almost always the target of his imagination. He liked these smooth-faced figures, and aloof behaviour that one could observe in bars. Every morning, he would spend a good hour arranging one or two photographs, jars, and a few violets, on a little table with a lace tablecloth, within arm’s reach […] Jacques Vaché, barely released from hospital, found employment as a stevedore unloading coal from barges on the Loire. He spent his afternoons in the dives that lined the port. In the evenings, he wandered from cafe to cafe, cinema to cinema, spending a lot more than was reasonable,

creating an atmosphere that was dramatic and full of enthusiasm, punctuated with lies and tall tales, which seemed to bother him little. I must admit that he did not share my passions and for a long time, I was just the ‘pohet’ to him, someone on whom the lesson of the epoch had had little effect. In the streets of Nantes, he would sometimes walk dressed in the uniform of a hussar lieutenant, an aviator, or a doctor. Sometimes, if he met you on the street he pretended not to know you and would continue on his way without looking back. Vaché didn’t shake hands by means of hello or goodbye. He lived in a nice room on the Place du Beffroi in the company of a young woman of whom I knew only the first name: Louise, ordered to remain silent and immobile in the corner whenever he welcomed me there. At five o’clock, she would serve tea and by way of thanks, he would kiss her hand. One imagined that he had no sexual relationship with her and was happy to merely lie next to her, in the same bed. In fact, this was how, he claimed, he liked to behave.’

by Mack Sennet, the first Chaplins, certain Al St. Johns. At this period I recall putting on an unrivalled footing a Diana la charmeuse […]. All we could grant of fidelity used to go to those serials previously so decried (Les Mystères de New York, Le Masque aux dents blanches, Les Vampires) […]. We saw in the cinema then, such as it was, a lyrical substance simply begging to be hauled in en masse, with the aid of chance. I think that what we valued most in it, to the point of taking no interest in anything else, was its power to disorient.’

The beginning of the letter refers to a prank carried out by Théodore Fraenkel who succeeded in publishing a poem about Pierre-Albert Birot in SIC, a review run by the latter, signing it Jean Cocteau.

Digitization of the facsimile in the 1949 K edition

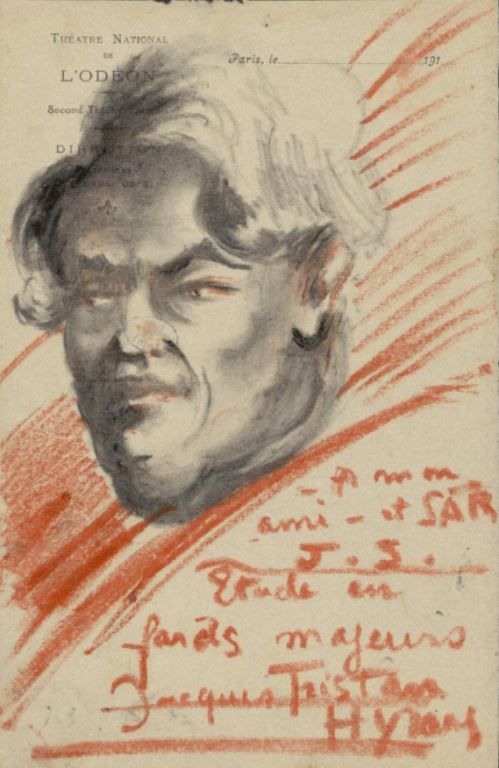

This drawing bears witness to Vaché’s encounter with Sarment at the Théâtre de l'Odéon where Sarment was performing in 1917.

Nantes Public Library, ms 3446/11

Sarment is the first on the right, Copeau can be seen on the extreme left, smoking a pipe.

Private collection

‘I saw Jacques Vaché again at the Conservatoire Renée Maubel. The first act had just finished. An English officer was creating a disturbance in the orchestra pit: it could only be him. The scandal of the representation had excited him terribly. He entered the room with his revolver in his fist and spoke about shooting at the public. To tell the truth, he had disliked Apollinaire’s “surrealist drama”. He thought the work was too literary and heavily criticized the costumes.’

responded to the first act with a great din. The reason for the growing disturbance in a precise part of the pit soon made itself clear to me: Jacques Vaché had just entered, wearing an English officer’s uniform: in order to look the part, he had taken out his revolver and seemed in the mood to use it. […]. Never before this evening had I taken the measure of the distance that separated the new generation from the one preceding it. Vaché, was exasperated as much by the good value lyrical tone of the play as he was by the Cubist rehashing of the decors and costumes, Vaché in a defiant stance against the public at once jaded and adulterated by these kinds of performances, was, at that moment, a revelatory figure.'

This is the copy that belonged to Vaché, conserved amongst his belongings after his death.

The programme, which includes an article by Guillaume Apollinaire entitled ‘Parade et l'Esprit Nouveau’, may be read on the website of the Library of Congress.

Private collection

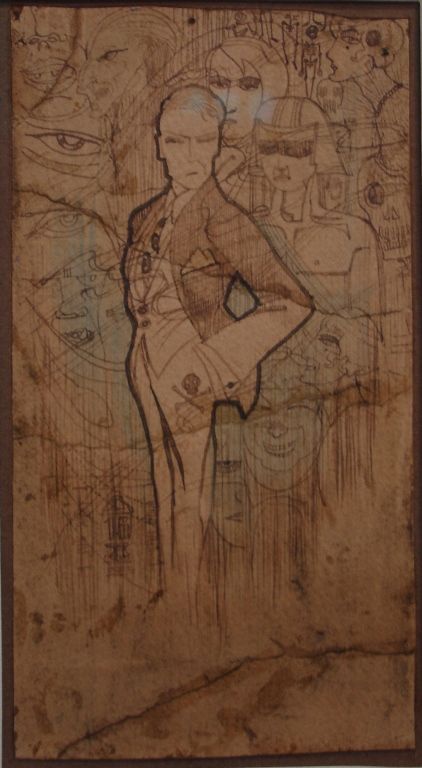

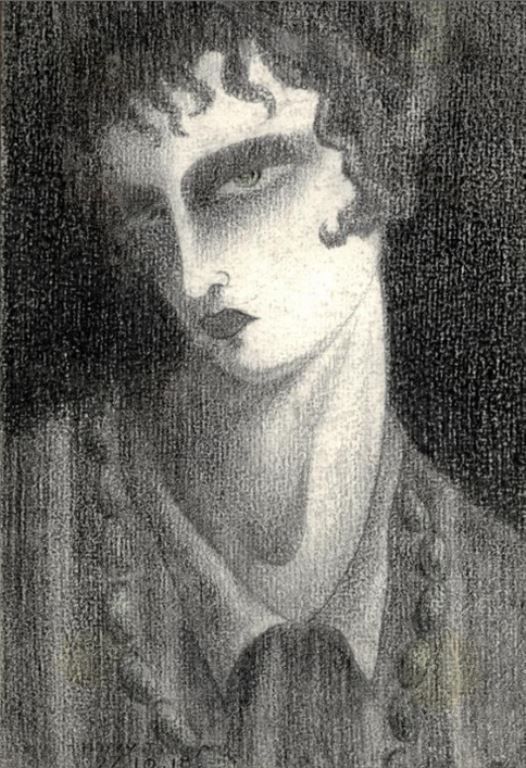

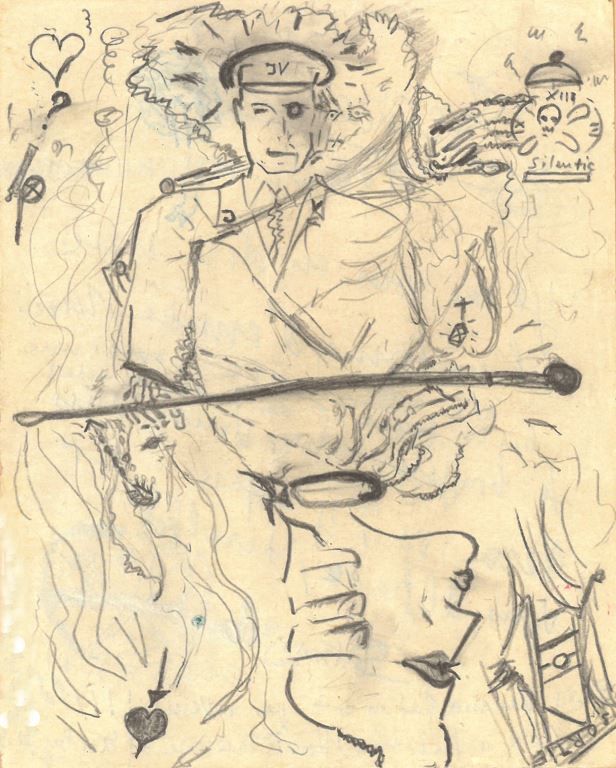

Vaché addressed this drawing to Breton in April 1917 and provided it with a title in a later letter. Breton published it in 1925 in La Révolution surréaliste under the title Jacques Vaché par lui-même (‘Jacques Vaché by himself’).

Private collection (former André Breton collection)

The original of this drawing by Vaché has never been found since its publication in the first edition of Lettres de guerre (War Letters). In La confession dédaigneuse (‘Disdainful Confession’), Breton indicates that Vaché presented him with this drawing in June 1917.

(Former André Breton collection)

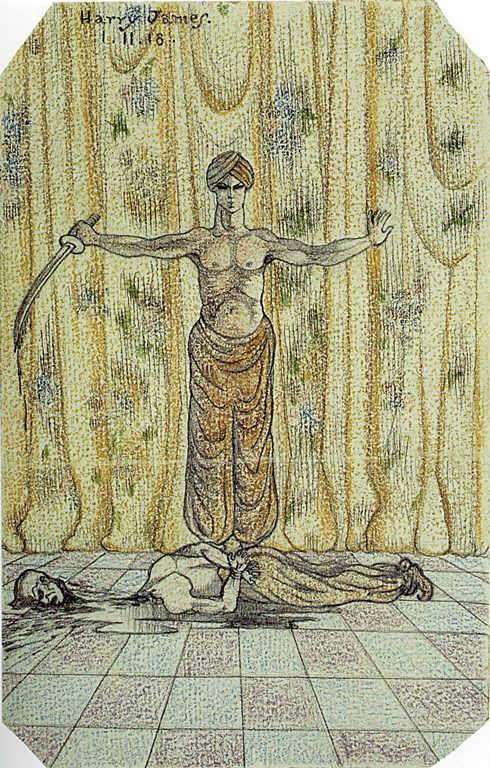

This drawing is part of a series which perhaps can be linked to a joint theatre project by both Vaché and Breton. In its execution, this series is reminiscent of Vaché’s pre-war drawings of the theatre.

Private collection (former André Breton collection)

Fashion drawing in which Vaché details in his notes the materials and colours of the clothes depicted.

Nantes Public Library, ms 3341

This drawing is signed Harry James, Vaché’s last known pseudonym with which he signed his last letter to Breton.

Private collection

Between October and December 1918, Vaché did four portraits of women, although it is uncertain as to whether these were executed using the same model. This drawing is also signed Harry James.

Nantes Public Library, ms 3573

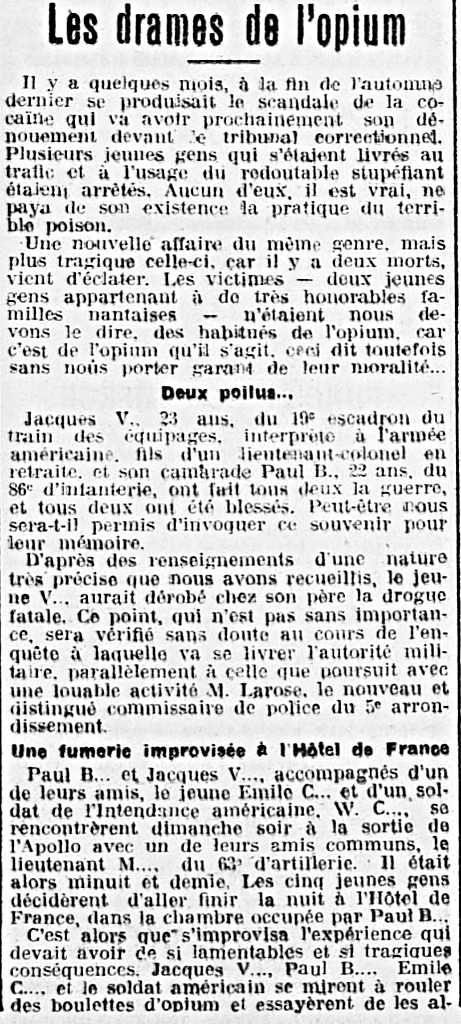

First part of the article devoted to the deaths of Bonnet and Vaché published in the newspaper Ouest-Éclair on 7 January 1919

Read on Gallica

Second part of the article on the deaths of Bonnet and Vaché published in Ouest-Eclair on 7 Jaunary 1919

Article published in Ouest-Eclair on 9 January 1919

Read on Gallica

‘Jacques Vaché committed suicide in Nantes sometime after the armistice. His death had this admirable feature about it, in that it can be taken for accidental. He absorbed, I believe, forty grams of opium, even though, as one might believe, he was not an inexperienced smoker. On the other hand, it is highly likely that his unfortunate companions were inexperienced drug users, and that he wanted in dying, to commit one last funny trick, at their expense.’

Jacques Vaché is believed to have declared several hours before the drama: “I will die when I want to die … but I will die with someone. Dying alone, is boring beyond words… Preferably I will die with one of my best friends”.’ ‘Such words,’ added M. Guégan, ‘make the hypothesis of an accident less certain, especially when one remembers that Jacques Vaché did not die alone. One of his friends was a victim of the same poison, on the same evening. They appeared to be sleeping next to each other when it was discovered that they were no longer alive. But to admit that this double death was the consequence of a sinister plan, means making the memory of one of these men terribly responsible.’ To trigger the disclosure of this ‘terrible responsibility’, was, most certainly, the supreme ambition of Jacques Vaché.

In the upper-left medallion, Desnos evokes Vaché’s death by associating the opium pipe and a postcard, symbolizing the hypothesis put forward by Breton of ‘the last funny prank’ concerning the supposed suicide of his friend.

Oil on canvas,

Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet.

Paul Nougé, J. Vaché. Satirical text published in La Révolution surréaliste (no. 9-10, October 1927), appropriating and altering a text by Rémy de Gourmont about the serial killer Joseph Vacher.

Read the full text on Gallica (the text is accompanied by two previously unpublished drawings by Vaché).

Nantes Public Library, ms 3994 (former André Breton collection)

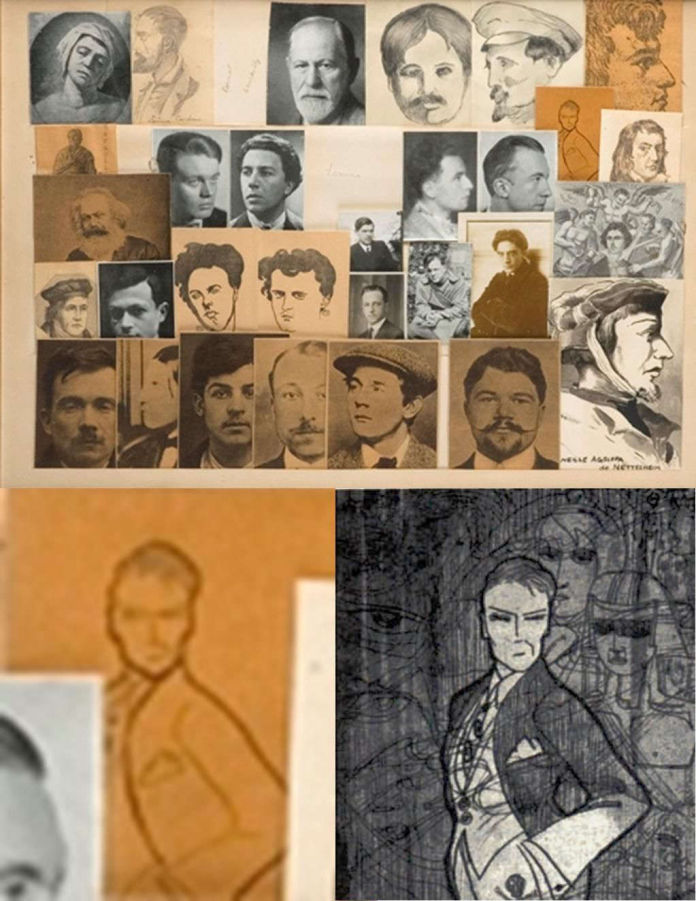

In this collage, Scutenaire inserts at the right-hand side, a sketch of a drawing by Vaché published by Breton under the title ‘Vaché par lui-même’ in La Révolution surréaliste. This collage appeared in the special edition on Surrealism by the review Documents in 1934.

Archives et Musée de la Littérature, Brussels..

Member of the Surrealist group between 1947 and 1948, Rodanski did this drawing during his internment at the Villejuif psychiatric hospital. He associates the only two portraits then known of Vaché. Rodanski’s literary work reveals his identification with the author of Lettres de guerre (War Letters). .

Archives du Groupe Hospitalier Paul-Guiraud, Villejuif.

Article by Lettrist Gabriel Pomerand published by the review Psyché in June 1948.

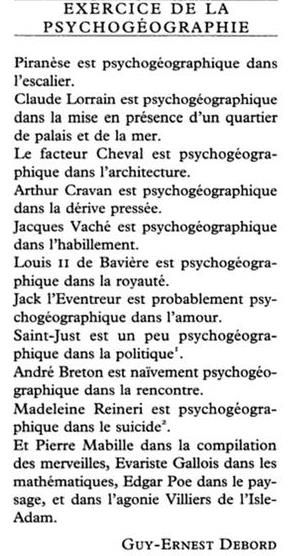

Published in Potlatch, the International Lettrist Review (the literary voice of the future Situationists), this text parodies the famous list established by Breton of the ‘surrealists in’ in the first Surrealist Manifesto..